Pinhole photography has a long and honorable tradition as a school project, as something photographers do for fun, and as a way to linger by creating long exposures in places where you want to hang out. There have been impressive works made with pinholes, but people usually choose it for the fun and back-to-basics simplicity of it.

I’d read that pinhole cameras have an “infinite” depth of field, and I needed to know if this is true. I’d previously made some tea-tin pinhole cameras for alt-process paper negatives, but the exposure times were far too long, and the results were underwhelming. It had also been a lot of work to make my own ‘film’ for the experiments. For my second round of experiments, I wanted something more likely to deliver reliable results that I could learn from, with shorter exposure times, and fast feedback.

Would you believe that Polaroid used to make pinhole cameras that have POLAROID BACKS? Using their peel-apart film products, you could buy either a hard-body camera or assemble a glossy cardboard kit, affix a machined pinhole plate to the front, affix a Polaroid Back (cartridge holder and rollers to spread the chemistry) to the rear, load the camera with a cartridge of peel-apart film, and make exposures with a bring-your-own-black-tape shutter. Pull the film through the rollers, wait for it to develop (under 3 minutes), and peel it apart to reveal your print. MAGIC!

Instant film pinholes!!! It all sounds so luxurious, outrageous, posh, – and also EXACTLY what I was after. Peel apart film was on the verge of being discontinued, so I was able to acquire the cardboard box version of this amazing set up affordably.

This was an educational experiment.

First: it is tough to use a camera without a viewfinder. Give the pinhole fans some credit for their great aiming guesswork!

Next, I learned is that the infinite depth of field story isn’t accurate for all pinhole cameras. There is a focal length for each pinhole that creates a minimum distance, and items placed too close to the camera will not be sharply focused. For people making pinhole cameras on small 35mm film and using tiny pinholes, it may seem like the depth of field is infinite, because their focal length is so small. In the case of this large boxy camera capturing images at the full size of a print by using a machined pinhole appropriate to making large images, the focal length is about the same as the camera box depth (perhaps four inches or ten centimeters), so my early determination to get super close was not a success.

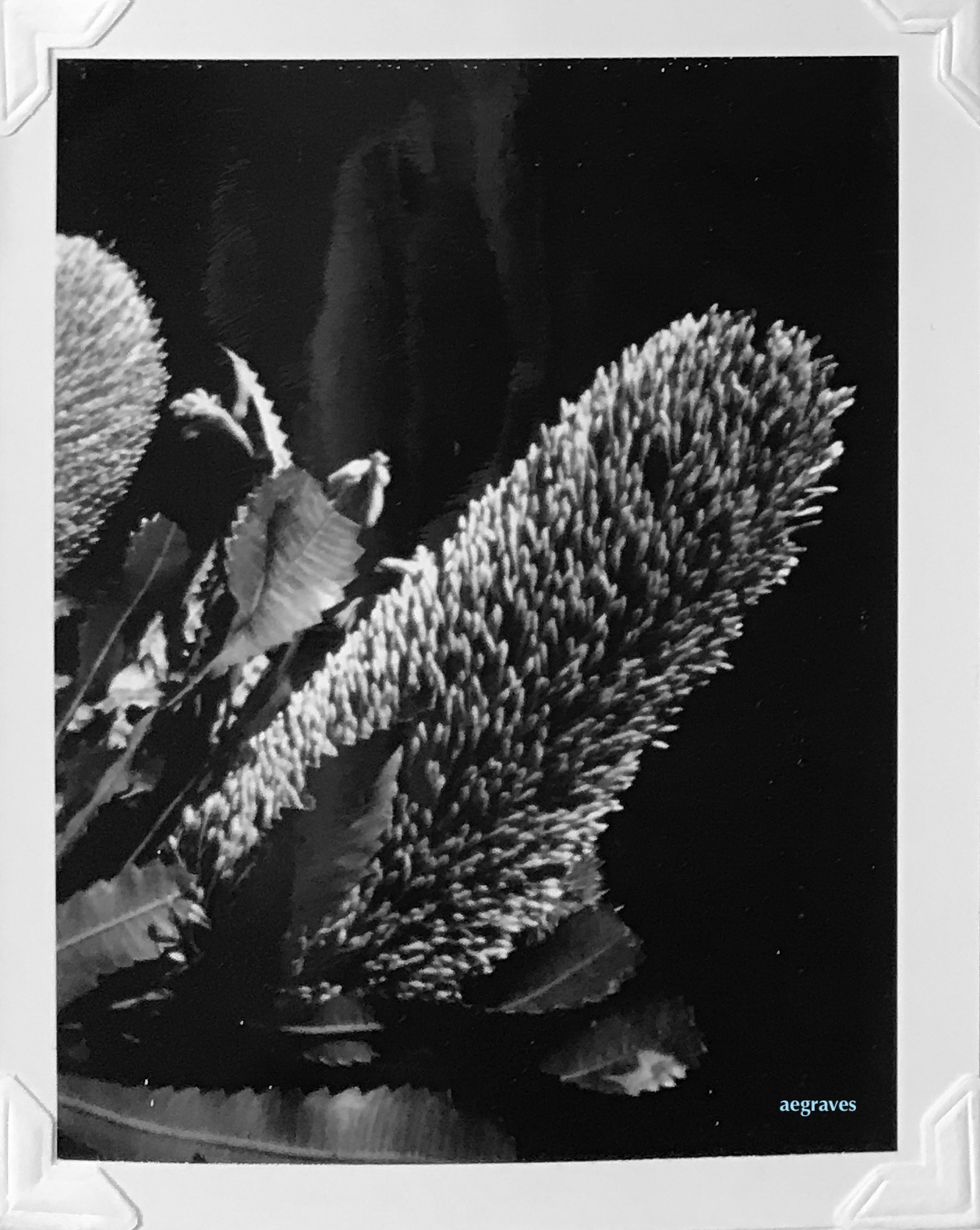

The recommendations that came with the kit gave me a good sense of how to start, and the instant (well, 3 or 4 minute) feedback helped me adjust my approach. I learned new things. I got to walk around town with an enormous blue box that screamed POLAROID in huge letters, advertising my geekiness. The contrast of the film was great, and my exposure guesses improved with time. I wasted at least one package of fast film without mastering exposures with it, and that’s okay – the slower film worked out. I learned that the color shift toward blue that others had described was a big factor in how color images come out, and decided I prefer black and white. I appreciate the results that others have gotten more now that I know how much guesswork and practice is involved.

This experiment did NOT make me a dedicated pinhole photographer. Without a truly infinite depth of field to expand my macro-photography, most of the allure of pinhole photography was lost. I expect cameras to offer something unique in their results, but my subject choices with my limited film supply meant that I used my pinhole camera conventionally, and it acted as a slow(er) normal camera.

Polaroid stopped making peel-apart films in about 2008. (This is why I am illustrating this post with photos from my archive.) As my supply of film ran low, I had to make a choice of how to use it: whether to use the film in my remarkable Polaroid 100 Land Camera or in my pinhole camera. The Polaroid Land Camera won, as you may have seen from my earlier post about its gloriousness. It is more versatile, and with film being so precious, I wanted to aim for the stars. The Land camera gave me delightful results, and was the right choice.

Earlier this year, my One Instant peel apart film order from Supersense arrived (after many COVID-related shipping delays), so I will have an opportunity to revisit my choices. Supersense’s peel apart film has each exposure in its own paper cartridge. This means pinhole images are now lower risk – I can take JUST ONE exposure, if the mood strikes, without committing an entire pack to the effort. This means I can try things I hadn’t had a chance to try before: long exposures at night are still on my to-do list. I hope to experiment and report in autumn.